More than 33,000 X users are following @victorEleDe. In some of his dubbings he parodies the kings of Spain and other personalities (journalists, politicians) and has often been the joy of the tweeting orchard. He used to do voice-overs with Google’s robotic voice, but now he has changed: he uses voice cloning so that, in his videos, the people he parodies appear to be saying what he wants them to say.

He may have lost some of his freshness, but his videos are still funny. However, when he switched to AI voice cloning something made me feel a bit like those La Codorniz published under the title “Tremble after you have laughed”. Would we be able to distinguish between a real and a fake audio of a personality, an actor, a politician, a prosecutor? From one of our close relatives? Honestly, I don’t think any of us have that fine an ear, and studies underline this.

There has been much warning about images (photo, video) called deepfakes, and there are good tools for detecting falsehood, but I think audio has almost more danger and destructive potential because of its enormous capacity to evoke images in our brains. If you regularly listen to the radio or podcasts you know exactly what I mean.

The voice-cloning is already being normalised and not always for the better. Or rather: everything that is invented for good can be used for evil, sooner rather than later. Their potential to interfere in electoral processes is, in my opinion, greater than that of deepfakes or mainstream misinformation. We still have no effective means to defend ourselves from it nor has its use been regulated: it may be useful for learning languages or scheduling medical appointments, but it poses a very high risk to democracies.

The crisis of truth

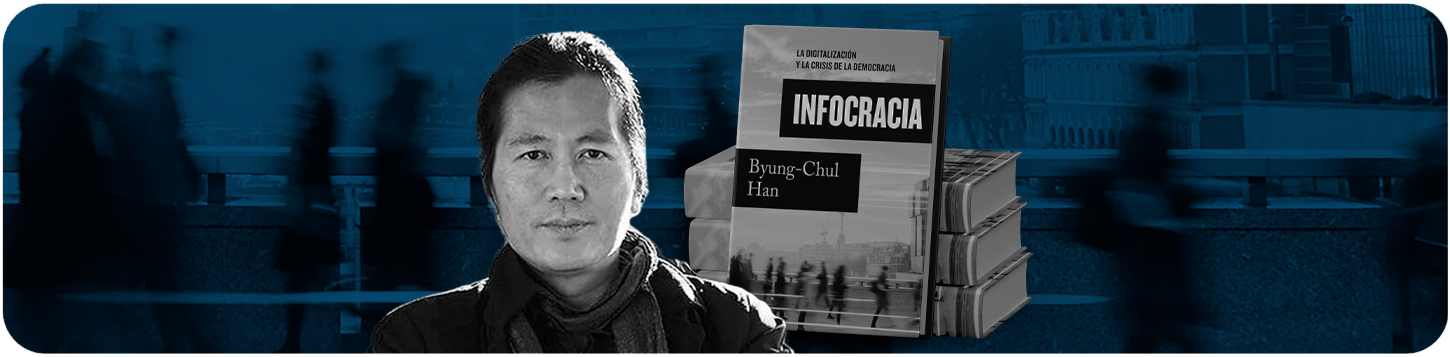

Truth is in crisis. Facts are known only through the senses, and if hearing and sight, which are our main ways of knowing what exists, are circumvented, we are more exposed than ever to lies and swindling. In his now famous “Infocracy“, Byung-Chul Han warns about the crisis of truth: we live, in his opinion, in a digital and therefore “defactified” universe, from which “the common world” has already disappeared, along with factual truths.

We need the truth. I return to Infocracy, where Nietzsche’s concept of truth is quoted, “a social construct that serves to make human coexistence possible“. Given the relevance of truth for coexistence and the need we have for a certain consensus around the facts in order to be able to work with opinions about them, it is difficult not to see the gravity of what we are experiencing.

The first Pedro Sánchez’s letter to the public had his party on tenterhooks for five days and the country for those same days and a few more in the corner of thinking about what’s going on with the disinformation. This debate existed until now for academia, the journalistic profession, communication, judges and politicians. A protocol was even adopted to combat disinformation in 2020.. And yet, here we are four years later, reading the letter from the president “deeply in love” that has finally taken the debate out of the academy and into the mainstream.

Disinformation training

Ramón Salaverría, to whom we will never be sufficiently grateful for his study and this talk in El Elefante Verde, spoke recently on El País on this issue. It was not the first time he referred to the need to educate the public and public decision-makers on how digital has taken lifelong misinformation to another dimension. The AI will take it even further, of this I am almost certain.

The BBC has started working on the issue in earnest and last March launched this new functionality to help your readers discern the veracity of your images and videos. Through a button on the screen, it tells you “how we verify this”, to understand the verification process carried out by journalists, a kind of making-of the news. This new functionality may need to become standard, and even then, there will be those who do not want to believe the truth.

I return to the Korean philosopher and his “Infocracy”: “The crisis of truth is always a crisis of society. Without truth, society disintegrates internally”. He adds: “Conspiracy theories thrive especially in crisis situations […] as micro-narratives that provide a remedy here”. I cannot refrain from also reproducing the following sentence: “Conspiracy theories resist verification by facts because they are narratives which, despite their fictitious character, underpin the perception of reality”. What can the BBC’s verification system, or any other, do against this reality?

We can all be victims of manipulation

As can be seen, this is not an easy debate. No one is comfortable with the assumption that they can be manipulated by third parties with bad intentions and relatively simple tools. It is not because we all think we are stronger and smarter than we really are, but because no one has explained to us the fact that no matter how smart or strong you are, you will always have a weakness to be attacked.

The only Spanish MEP who has participated in the recently approved lEU AI law, Ibán García del Blanco, has many interesting things to say as a result of his participation in this extremely important legislative work. Among them, one of a very political nature: the future (or perhaps already present) debate will not be polarised around left and right, but around two poles that no one would have imagined just a few years ago: those who respect the institutions of the liberal democracy and those who do not value, nor want, that institutionality. Perhaps that is why the European Parliament campaign for the upcoming elections has as much to do with a serious warning to young people about what the dictatorships and totalitarianisms. It is the young people who will live the longest in the EU that will be voted on Sunday 9 June, and who should have the most interest in the European elections; and yet they are the ones who are most easily demobilised by messages for them in social media, which are pure disinformation and anti-politics.

In short, and to conclude, there is an urgent need for literacy education about the disinformation that threatens their security and their freedom to choose their representatives, but no less urgent is literacy education also, as Carmela Ríos tweets, people much less humble, the one who has to decide who are journalists and who are, not just agitators, but manipulators of the will of the people.

This issue cannot be regulated without a thorough understanding of what disinformation is and how it works in these digital times. The problem now is whether those who are going to regulate us will admit their lack of understanding of this complex phenomenon, will sit down and listen to the experts, and will be able to regulate it without infringing on fundamental rights.